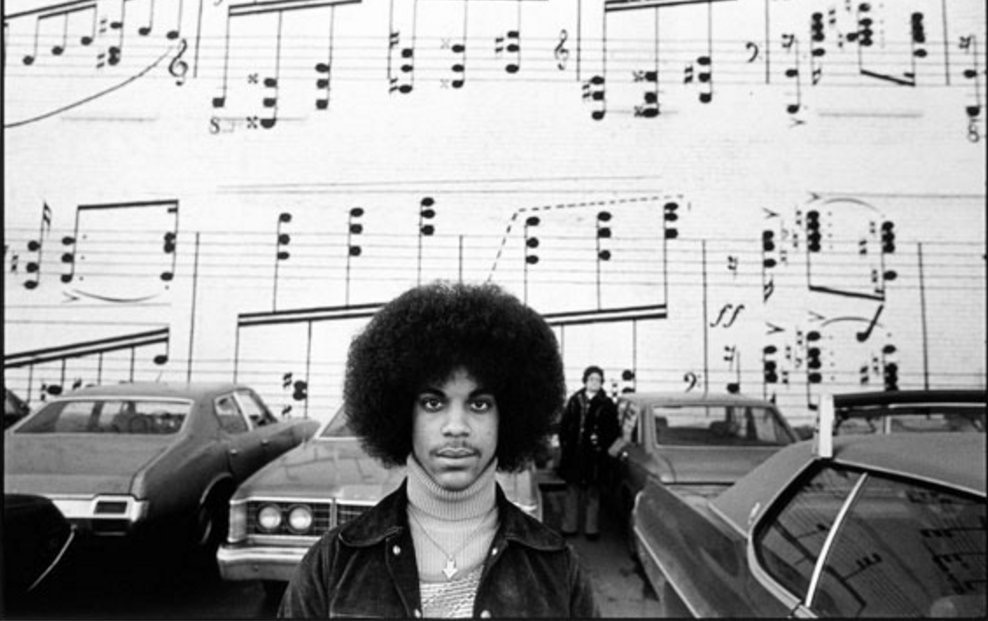

When it Snowed in April

By M. Abduh

Dearly beloved, we are gathered here together to get through this thing called life. —Prince

IT SNOWED this year in April. Large flakes that fell like confetti. My daughter called me from somewhere downstairs. She knew I was writing. She knows not to disturb me. Did she lose a toe? I thought. Even so, this girl knows better. “Daddy, it’s snowing outside!” she called up again. I work in what was once a walk-in closet I call “the hole,” not as dark or damp as solitary confinement, but certainly as cramped, and just as cut off from the world. It was another morning of struggling, sweating over the keyboard like prison labor, and I probably would have been more productive pressing license plates. I rose and went into my bedroom and parted the blinds, to watch the ticker tape. It’s April, I remembered in the moment, then I remembered Prince’s song “Sometimes it Snows in April.” I hadn’t heard it in forever, and the lyrics were like so many other memories: the lingering scent of something. But I could remember the chorus, coming up to me as loud as my daughter’s voice from somewhere downstairs:

Sometimes it snows in April

Sometimes I feel so bad

Sometimes I wish life was never ending,

And all good things, they say, never last

The NBA playoffs distracted me from the news of his demise. Running late to the university for my 2 p.m. class, I was listening to an ESPN podcast on my phone. My sister, who was dropping me off, was listening to the car radio. I had in my earbuds, but she must not have known I had something on. (How these devices help us ignore each other.) We were crossing the Walt Whitman when she said something to me. I thought she might be badmouthing the toll booth operators again. I nodded, half smiling, pretending to hear her. When the guy in the toll booth took my ten-dollar bill, he swiped it with a marker and held it up to the light, long enough to count every line in Hamilton’s face, then counted my change three times. How long does it take to count five ones? I thought. A dollar a minute it appears.

Despite delays, I arrived to class a few minutes early, and there were only a handful of students present, scattered to the four corners of the room. I answered questions about their essays and checked my text messages. One from a friend said simply: “Prince (crying emoji). I’m so sad.”

Prince?

I went to Twitter (where one goes for news nowadays), and there it was: SINGER SONGWRITER PRINCE DEAD AT 57.

Can’t be real.

The public is always killing off their celebrities, only to resurrect them later in a hologram. I sent my sister a text message:

“Hey, you heard Prince died?”

“Yeah. It was on the radio. I mentioned it to you while we were in the car.”

The students continued to trickle in and take their seats, and I continued to answer questions about grades, problems with their papers: vague thesis statements and awkwardly worded sentences, but I was hearing voices from the beyond:

Come back, Nikki, come back! —

I guess I must be dumb, she had a pocket full of horses—

Dorothy made me laugh. I felt much better, so I went back to the violent room…

For the entire lecture, while I whitened the chalkboard with active verbs and transitions, all I could think of was Apollonia coming out of the water, soft and wet, and Prince telling her, “That ain’t Lake Minnetonka.”

***

I used to cry for Tracy because he was my only friend

Those kind of cars don’t pass you every day

I used to cry for Tracy because I wanted to see him again,

But sometimes, sometimes life ain’t always the way

It must have been five years ago, when I last spoke to AJ, my best friend from high school. He’d moved away years ago. We’d been in and out of touch probably a dozen times over the years. We laughed about old times, especially our first encounter. Not long after he moved to the neighborhood, he came to the field where a bunch of us always played football, or “kill the man” to be exact. In “kill the man,” everyone crowds around the ball, then one of the players throws it up for grabs. Whoever catches it has to try and make it to the goal line—alive; the other players try to kill him before he does. The game invariably ended in torn up shirts, scraped up knees—and shit talking. AJ was new, so while he might have gotten away with a tear or scrape, shit talking was strictly for those missing teeth in your elementary school pictures. So a couple of us jumped him. But truth be told, we didn’t beat him bad enough to stop him from talking shit.

It’s an old story: you fight, then become lifelong friends. And though our friendship didn’t last a lifetime (it didn’t last much past graduation), in those days we were inseparable. One of the things that made us so close was our mutual love of music. AJ was a drummer. He would constantly tap beats on his desk in class, the lunch table, parked cars, and finally on a set of drums he’d saved up for. I was a rapper who scrawled rhymes all over scraps of brown paper bags and envelopes. AJ tapped beats, I freestyled. We shared not only a love for music in general, but an obsession with Prince in particular. AJ talked chords and bridges. I talked metaphors and images. We would sit for hours on my family’s green crushed velvet couches and listen to Prince records. “Yo! You hear that?” was a constant refrain. I must have repeated that ten times when we first heard “Raspberry Beret.”

The rain sounds so cool when it hits the barn roof

And the horses wonder who you are

Thunder drowns out what the lightning sees

You feel like a movie star

Not your average pop song poetics: synthesia, personification, narrative full of characters like poor, passive-aggressive Mr. McGee, and the narrator’s unnamed love interest, a woman so free she walks into that shop, and into a one-night stand, through the out door. “Built like she was,” he says, “she had the nerve to ask me if I planned to do her any harm.” And in my teenage mind, I thought: Damn. She must be like Thelma from Good Times. Prince’s words put us there: in the five and dime, at Old man Johnson’s farm, in that barn. This was my first introduction to imagistic writing, well before I heard of an Ezra Pound or H.D.

Those Prince listening parties continued throughout high school, as he dropped an album every year: Purple Rain, 1984; Around the World in a Day, 1985; Parade (my personal favorite), 1986; Sign o’ the Times, 1987; Lovesexy, 1988.

Then, in our senior year, right around graduation, Michael Keaton took on the role of the Caped Crusader in Tim Burton’s Batman (darker than the onomatopoeic fist fights of the old Adam West series). Prince supplied the soundtrack, and the single “Scandalous” alone was worth the price of the ticket. Unfortunately, that album would be the end all. I left for college in Brooklyn at the end of the summer. AJ went into the Air Force. I hadn’t really thought much about any of this in those five years.

Then Prince died.

One of my first thoughts after receiving the news was of my old friend. I wondered how the word reached him. How he reacted. If it took him back to those green crushed velvet couches again.

***

Springtime was always my favorite time of year,

A time for lovers holding hands in the rain

Now springtime only reminds me of Tracy’s tears

Always cry for love, never cry for pain

On his HBO special Never Scared, Chris Rock says, “Whatever music was playing when you started getting laid, you gonna love that music for the rest of your life,” but love really is too weak to define just what Prince’s “Adore” means to me; the song that got me leg-locked in the slow drag of a lifetime with my teenage love. Staci was a Nia Long, before Nia Long: caramel complexion, slim, with a cute mole above her lip. She looked soft-spoken, but when she opened her mouth, it came out deep and raspy, too deep for a girl her size. It was almost as comical as hearing the devil come out of the little girl in the Exorcist. Whatever. Possessed or not, Staci was gorgeous.

In the summer of ’87, we threw a party in a run-down community center: no door on the toilet stall, spider web cracks in almost every window, and a dirty, scuffed up sardine linoleum tile dance floor. The center’s staff made sure the bar along the back wall was dry, since we were minors, but there were bottle-topped brown paper bags everywhere. We charged whatever dollars we could. My man Bun, who was big as Refrigerator Perry, was at the door collecting the money and marking hands. I knew Staci was coming and told Bun to make sure he got me before letting her and her girlfriends in.

It was loud in the in the hall—loud music, louder talk, and the usual huddles of different neighborhoods planning a melee. A little after eleven, AJ tapped me and pointed to the door. Bun had his hands up like he was about to start juggling. Behind him in the doorway was Staci in a bright turquoise blouse. It made the hall even louder. I came over and took the marker from Bun. “I have to charge you extra,” I said. Her head snapped back, and she squinted until there was almost nothing but lid. “Boy, stop playing!” I put the cap on the marker and leaned into her ear, “It’s because of that shirt. You gon’ have the electric bill sky high.” She slapped my shoulder. “You know you like it,” she said.

I did.

I told her, her sister and girlfriends they didn’t have to pay, and marked Staci’s hand. “You owe me a dance. A nice slow one,” I said.

“I’ll just pay then.” She smiled, and her sister and friends pulled her into the fray. Bun shook his head, “You paying for all them?”

We had to end things by 2 a.m. So around one, I gave AJ the word to put it on.

The applause of a crowd, organ grind…

Until the end of time…

I reached through her girlfriends and pulled Staci out by the elbow (like a camel through the eye of a needle).

I’ll be there for you…

”You think you slick,” she said in my ear. She leaned back and pointed to the then smeared phone number I wrote on her hand when she came in.

If God one day struck me blind…

“That shirt I’d still see,” I sang over the lyric.

She stopped dancing. I pulled her in closer. She put her cheek on my chest and wrapped her arms around the back of my neck. She smelled like a combination of pink lotion and sweat. I ran my hands down her back. She felt even smaller than she looked, like I could have strummed along on her ribs.

I truly Adore you…

“I’mma take you home after this, all right?”

She sucked her teeth and rocked low.

“I love this song,” she said.

“I know.”

***

All good things, they say, never last

And love, it isn’t love until it’s past

Musically, in our house, for everyone under forty my big sister was the tastemaker. She was our gateway to hip hop, blasting Lady B’s rap show on WHAT Saturday afternoons until the signal faded. She always had the new records first: Spoonie Gee’s “Love Rap,” Kool Moe Dee and the Treacherous Three’s “Heartbeat,” and the heaviest spun album in her collection: “One Nation Under a Groove” by Parliament-Funkadelic. A congress of horns, synthesizers, guitars, banjos, and congas. I was drawn not only to their music, but the wild cover art, an alien band raising the R&B flag high above the world. To some, they were out there, otherworldly, but their funk came from home, out of the earthly sojourn across continents, oceans, and plantations, migrating north to a barber shop in Plainfield, NJ, inspired by James Brown, Hendrix, Sly and the Family Stone, and in turn inspiring generations to follow—among them, Prince.

When Parliament-Funkadelic was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1997, the Artist (as he was known at the time) said as much when he spoke of George Clinton’s overarching influence: “I went to see him at the Beverly Theater, and it was frightening. Fourteen people singing knee-deep in unison. That night I went to the studio and recorded “Erotic City.” Needless to say, he’s been an influence on me and everyone I know…That’s all we groove on.” And it was true; their sound would funk up every record from Three Feet High and Rising to Straight Outta Compton.

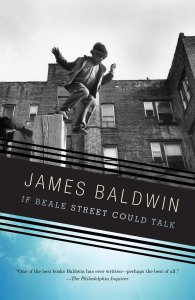

And just as my sister introduced me to hip hop and funk, I first heard Prince after shuffling through the stacks of records piled up beside her bed. My favorite then was “Little Red Corvette” on the 1999 album. The cover art was as psychedelic as Funkadelic: a star-clustered purple sky, with eyes in the 9’s staring back at me. I would play that song over and over, too young to know anything about one-night stands or the metaphors Prince was using to describe them, but I loved the synthesizers, the drums, the echoing claps, and most of all, the guitar solo. I had a not so well kept secret in those days. For all the hip hop, funk, and R&B of my house and neighborhood, I loved hard rock. (Jazz I rejected as my “father’s music.” It wouldn’t be until my twenties that I gained an appreciation for the genre.) I was a huge KISS fan, introduced to their music by a white kid from school named Adam. The secret earned me the nickname “White boy” with my cousins, aunts, and uncles. It would be years of teasing before I would learn that the roots of this genre went back not to white boys, but to our Blues People, guitarists like Lead Belly, a favorite of Kurt Cobain. So when I heard that guitar solo on “Little Red Corvette,” I was happy to know I wasn’t the only white boy. I played that record until I put a scratch in it. Halfway into the song, it would skip all the way to the end, well beyond the rubbing alcohol remedy. I knew better than to be in her records when she wasn’t home, just like I knew better than to mumble a word about scratching one of them up. That, too, would remain a secret until the day Prince died.

When my sister picked me up that evening after classes, we talked a little about nothing for a few traffic lights, and then I said: “Prince. Ain’t that crazy?” She shook her head in disbelief. “It’s all over the news. I’m going to watch Purple Rain tonight.” I turned down the radio. “Hey, guess what? You know…Remember your 1999 album got all scratched up…?”

“And you, what…say something thirty years after the fact? I should have known it was you. I blamed everyone in the house but you—What is it $9.99 on iTunes?” she said.

“I got you,” I said laughing.

“I loved that album,” she said.

“I know.”