A Joyless Noise

By M. Abduh

IGNORANCE OF A THING does not make it nonexistent. For years, we have witnessed a bank of talking heads—sportscaster and journalist Stephen A. Smith most recently—ask: “Where is all the noise about black lives mattering when blacks kill other black folks?” A good question is often half the answer, yet here the questioner has started in the negative. To begin, the very concept of “black on black crime” ignores the fact that murder, assault, theft, etc. in the main are crimes of opportunity—and proximity. Thus, by and large, the rapers of white women are white men. With that, and the fact that white men are statistically far more likely to be mass shooters, there exists nothing in our discourse called “white on white crime.” And as for the claim that blacks do not make noise when their killers are black, then Mr. Smith & Co. need reminding that the devil is a liar.

Noise has been made, in song, in literature, in film. One need look no further than the Stop the Violence Movement of the late 1980’s. After the death of a fan at a concert, artists like KRS One and BDP, along with Stetsasonic, Kool Moe Dee, MC Lyte, Doug E. Fresh, Just Ice, Heavy D, and Public Enemy came together to create the anti-violence anthem “Self-Destruction.” The song spoke specifically to “black on black” violence. Kool Moe Dee (of Busy Bee fame) states,

Back in the 60’s our brothers and sisters were hanged.

How could you gang bang?

I never ever ran from the Ku Klux Klan

And I shouldn’t have to run from a Blackman

Moe Dee’s lyrics are clear. The reader need not refer to Rap Genius for an annotation. Here the violence perpetrated by Amerikkka’s most viscous domestic terrorists, the Klan, who hung, raped, castrated, bombed, and burned black flesh—because it was black flesh—was not his immediate threat; instead, it was the flesh of his flesh chasing him. Also, in the song’s music video, during the late Heavy D’s verse, we see the message: 84% of violent crimes against blacks were committed by black offenders… crawl across the bottom of the screen. And while the numbers are quite similar for whites committing crimes against other whites (83% of white murder victims are killed by other whites), to Mr. Smith’s point, people in the black (and hip hop) community have always made noise.

After those artists came together on the East coast, a number of their peers on the Westside, artists like King Tee, Body & Soul, Def Jef, Michel’le, Tone-Loc, Above The Law, Ice-T, Dr. Dre, MC Ren & Eazy-E, Young MC, JJFad, Oaktowns 3.4.7, Digital Underground, MC Hammer united to create the song “We’re All in the Same Gang.” Addressing the gang bloodshed, and “fratricide” taking place in LA; these artists created a song with a message similar to that of “Self Destruction,” and like “Self Destruction,” “We’re all in the Same Gang” addressed brothers killing other brothers:

Kill a black man?

What?

Yo, what are you retarded?

Tell ‘em Hump

Do you work for the Klan?

Do what ya like

Unless you like gangbangin’

Let’s see how many brothers leave us hangin’

Humpty Hump of Digital Underground reasons that these black killers might as well be the in the same gang as the Ku Klux Klan, and in the song’s video, when reciting the last line, he pantomimes being hanged at the end a rope, likening this black on black lynching to the strange fruit Billie sang of. In the years that followed these two songs and movements, there arose a number of artists who continued to scream us awake, from them, New Rochelle’s Brand Nubian. Their lyrics, samples—their very name—spoke not only to black pride and “knowledge of self,” but self-preservation as well, with songs like “Wake Up” and “I’m Black and I’m Proud. Brand Nubian’s Grand Puba says,

Do the knowledge, Black

Look at the way that we act

Smoking crack,

or each other with the gat.

The only race of people who kill self like that

I deal with actual facts to keep my mind on track

Of course, when we do the knowledge, actual facts show that every race of people kills self like that. Maybe Mr. Smith was not a Brand Nubian fan. Ice Cube, perhaps? In his song “Us,” from his classic album Death Certificate, the voice of the song excoriates the perpetrators of what he deems pathological, self-destructive behavior: “And all y’all dope dealers/you as bad as the police, cause you kill us.” So just as Kool Moe Dee and Humpty made comparisons between “black on black crime” and the terrorist violence of the Klan, Cube here juxtaposes extrajudicial killing at the hands of state agents and proxies, sworn to serve and protect the citizenry and backed by the powers that be, with crimes committed by…us. And so it does not appear that we are stuck in nostalgia, citing verses from hip hop’s “golden era,” we also hear these voices echoed today by artists such as Compton’s own Kendrick Lamar. In his song “The Blacker the Berry,” he says,

So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street,

when gangbanging make me kill a nigga blacker than me?

Hypocrite!

For Lamar, the shedding of tears (perhaps even marching, raising voices, etc.) when a black man is killed by whites, but not doing so (allegedly) when the gunman is black smacks of hypocrisy. On that same note, in an interview with Billboard, Lamar states: “What happened to [Michael Brown] should’ve never happened. Never. But when we don’t have respect for ourselves, how do we expect them to respect us?” It’s all there. Black pathology. Respectability. Hypocrisy. Mr. Smith, holler if you hear him.

Rappers have not been the only artists to speak on it. After the Blaxploitation films of the 70’s, heroes and sheroes like Shaft and Foxy Brown “taking it to the man,” the 80’s gave us black street culture in films like Beat Street, Breakin’, and Wild Style. Then in the 90’s, black filmmakers explored not only the subject of police brutality and the injustices of the criminal justice (just us) system, but “black on black” crime as well. John Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood opens with the voices of a group of young men: angry, cursing, Black: “Yo fuck that. Where my strap?” Alarm chirps, car engine starts, revs. “We fin to let these niggers have it.” Guns click, tires peel—more curses—and finally, machine gun funk. The screen fades to black and there appear the words: “One out of every twenty-one Black American males will be murdered in their lifetime. Most will die at the hands of another Black male.” This opening sets the tone: black men die young, they die violently, they die at the hands of other young black men. This theme runs through a number of the films of the decade: Menace to Society, South Central, Clockers, etc. (Today, in 2015, Spike Lee has again focused on crime’s black hand in his latest film Chiraq, repeating in interview after interview that it doesn’t matter to the family of victims what color finger pulled the trigger.) So either Mr. Smith “don’t know or don’t show” what these films are saying.

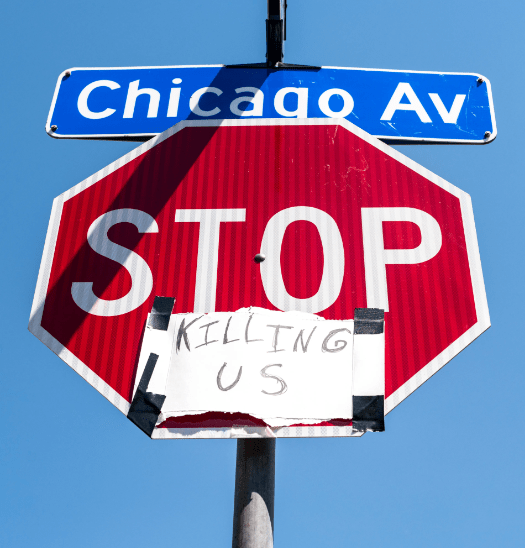

In 2012, Atlantic Monthly correspondent Ta-Nehisi Coates penned an article entitled “Why Don’t Black People Protest ‘Black on Black’ Violence?” The article came as a result of a question posed by some after the death of Trayvon Martin: “But what about all the other young black murder victims?” meaning, at the hands of other black people. In the article, Coates lists a number of anti-violence rallies that had taken place in cities from Chicago to Brooklyn, stories of residents and community leaders—weary of laying their dead to rest, and laying stuffed animals where they died—who organized marches, prayer circles, candle light vigils, and “take back the street” protests. Reading of—and indeed, witnessing—these gatherings year after year in neighborhoods across the country is indisputable proof of the great effort to cry out about the violence. Thus, for Stephen A. Smith to ask where is all the noise about black lives when blacks kill one another is a clear demonstration of his tone deafness, or perhaps he cannot hear due to his constant ranting, which often resembles a child sticking his fingers in his ears when he doesn’t want to hear what’s being said: La-la-la-la-la-la! For him to speak as if these dedicated marchers and organizers, mothers and sisters, husbands and wives, co-workers and classmates have been mute, in some perpetual moment of silence, as opposed to urging and exhorting their children and kinfolk in the streets is contemptuous.

Many Black writers, journalists, & cultural workers remain in the tradition of Ida B. Wells, documenting state violence against black bodies, giving voice to the unheard, speaking truth to power concerning incident after incident of unpunished killings & unindictable killers. They also remain in chorus with the aforementioned organizers and marchers against neighborhood violence. Perhaps if Mr. Smith would hush his ranting, remove the fingers from his ears, and listen, he could hear the noise of protest.