It Was Something He Said

By M. Abduh

Truth be told, I sometimes wish I could avoid doing readings altogether. What I’m certain comes off as awkward and perhaps even antisocial behavior is simply a writer who has gotten quieter and, inexplicably, shyer in recent years. Moreover, I absolutely do not like to be photographed. But despite such Salingeresque eccentricities— and pleas to audiences—social media and cell phone cameras do not allow anyone who stands in, around, or in front of an audience any such reserve. However, when a fellow poet was sick in the hospital and asked me to read in his stead, I reluctantly agreed. Understand me. No matter my reluctance, I recognize the importance of reading poems aloud. Reading aloud is poetry. An oral art form should never be reduced to mere characters on a page.

When I arrived at the venue, the event’s organizer asked if I could read for at least fifteen minutes. I had brought about six poems: three I had read before audiences, two newer pieces, and one by another poet. One was about my grandfather, a lefty who pitched briefly for the old Negro leagues, a poem about the 1967 North Philadelphia uprising, another about the MOVE bombing of Osage Avenue, and one about my young daughter’s preference for white Barbie dolls. The other piece was new, rough. It needed some reworking, but I wanted to hear it aloud, not just scratch and scribble at it in a notebook.

I leaned into the microphone: “The next poem I want to read is a new piece, “That Nigger’s Crazy.” Audio feedback accompanied the title, and the faces in the audience—mostly white—stiffened like a totem. Shock was not the intent. But it was not unwelcome either. I should mention that I am not from the school of thought that believes the word “nigger” has somehow been transformed from a viscous racial epithet, rooted in a wicked tradition of slavery and Jim Crow, to a term of endearment. As author Maya Angelou articulated to Dave Chappelle, if you take poison out of a bottle marked with a skull and crossbones and pour it into the finest Baccarat crystal, the decanter could never turn poison into wine.

Furthermore, I am not from those who get some sort of pleasure from hearing the word, especially from white folks who other Blacks swear to me are “down by law.” And contrary to the efforts of recent generations, overuse has not diminished its deadliness. But the poem is not about the word “nigger” or how uncomfortable it makes white (or some Black) folks. It is about the artist who most influenced me as a poet and whose work is why I pursued a writer’s life.

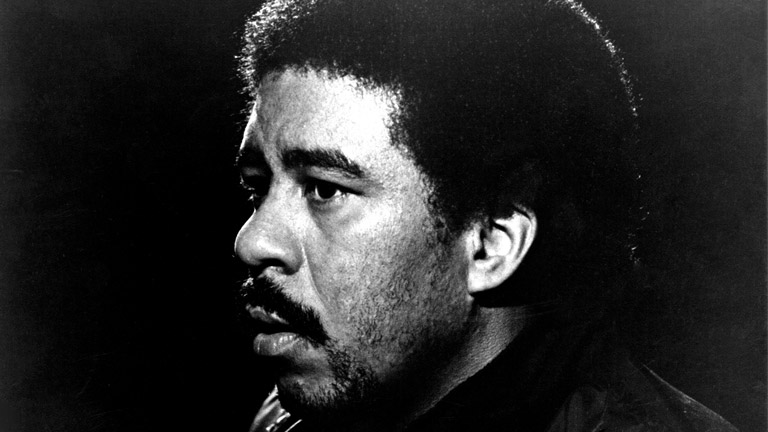

Sit with any group of writers, poets, playwrights, and the subject of influences will inevitably come up: “Who’s impacted your work the most?” When asked this question, most poets I know invariably list other poets: Sylvia Plath, Charles Simic, Countee Cullen, Gwendolyn Brooks. “Since hearing the rhythms of ‘Howl,’” they say, “I haven’t been able to put down the pen.” Years later, I could claim that a line from an Amiri Baraka poem inspired me to write, but my love of language began much earlier. It took root in the basement of my family’s South Philly row house, where, as a kid, I would tiptoe into the basement after my parents went to bed (or when my father dozed off on the couch after a taste or two), fumble with the glass door knob, and creep into the red-bulb-district. A stubbed toe on the washing machine echoed through the house. The boiler in the back room fired up, rumbling like a dump truck. I flipped through the albums in old milk crates, and there it was, between Donny Hathaway and the Ohio Players: That Nigger’s Crazy. On the cover, with a puffy natural and wild eyes, was Richard Pryor. I lowered the volume until I could barely hear the needle scrape under my finger. After the record player’s arm floated over the rotation, it dropped cleanly in the grooves and crackled: Please put your hands together and give a big round of applause. Mr. Richard Pryor! And after the cheers and applause came the voice of a supplicant, “Hope I’m funny.” And for the next thirty-three minutes and thirty-five seconds, his prayers were answered.

Looking back on it now, I cannot understand why our parents hid those albums from us. It couldn’t have been the cursing. My father’s language was harsh enough to make even Pryor say, “That motherfucker needs to watch his mouth.” Cursing was my old man’s way of punctuating his sentences. “Fuck” was an exclamation point, “Shiiiit” a period. It also couldn’t have been the characters Pryor spoke through. My entire neighborhood was on those albums. When Pryor did the routine of a drunk in a bar, it was like watching Uncle Bill stumble on the corner and start a fight in front of the 23rd St. Lounge. When he performed his routine about police profiling, it was like seeing my father nervously eye the rearview mirror as a squad car’s flashing lights pulled us over on the Atlantic City Expressway. “I-am-reaching-into-my-pocket-for-my-license!” Pryor exclaims to the officers, “Cause I don’t want to be no motherfuckin’ accident.”

As a youngin’, Richard’s blue humor is part of what brought me to the basement, but as I grew, I began to hear something beneath it all, a richness of language, a vocabulary that not only talked shit, but snorted coke, threw fists, cried out for justice, and bled. It has been said that life is comedy on the surface and tragedy underneath, and beneath Pryor’s comedy, there is plenty of tragedy and pain—not just his personal pain, but the pain carried in the dry bones of ancestors. But Richard knew cures. He was a healer who could make you laugh until your belly ached. He was Bowjaws of the bayou (let Bowjaws handle it!), Blackula on the block. He found the wino’s wisdom, the junkie’s humanity, and America’s ironies. His comedy, after all, was forged in the tempest of the struggle. This is why Dr. Cornel West said that Pryor was “the freest black man of the 20th century.” I found in those albums an insight into the American race problem as profound as any I have read or studied since. I know there are some so devoted to the “canon” that they would laugh harder at my last comment than they might at one of Pryor’s most brilliant routines, and, of course, they would retort that no American has touched the humor and satire of Mark Twain. But as Paul Mooney said, “If Mark Twain is the greatest, then Richard is Dark Twain.”

As a teenager, no longer forced to sneak around basements, I listened to every album I could get my hands on. I traveled to New York to procure the most obscure recordings of Pryor available. I recall one in particular where he satirized the radical poets of the late 60’s and early 70’s. In the routine he took the stage in the personae of a poet who stood before his audience and said, “I want to read a poem for you, it’s a new poem, and I hope you enjoy it.” Pryor pantomimes the poet reaching into his pocket slowly, careful to keep eye contact with his audience. He unfolds the paper deliberately, takes in a deep breath and yells at the top of his lungs, “BLAAAAAAACK! Thank you very much, ladies and gentlemen.” No doubt he playing on the stereotypical image of poets from the Black Arts movement, but clearly he recognizes not only the power of the word “black,” but also the role of the poet in delivering that word to the masses. And Pryor had something else in common with his character. He, too, was a poet. I don’t mean a poet in the way Baldwin understood it. I mean POET. In an article on some of the questionable choices the comedian made in taking on certain film roles, writer Ishmael Reed states, “He wrote poetry and I asked to publish some, but he was shy about exposing this gift.” That shyness notwithstanding, I was able to find some of Pryor’s poetry; in particular, a radio broadcast he conducted in 1971 on KPFA in Berkeley, California. The broadcast comprised a series of programs addressing the atrocities of the massacre at Attica State Prison in New York that year. During the program, a somber Pryor read a poem he had written in protest of the incident, a thoughtful, intense elegy to the black men who were gunned down in that prison yard:

Murder the dogs!

The mad frothing at the mouth dogs

with expensive capped teeth

and fat bellies full of babies starving.

No, don’t wait until they die, kill them now,

because if you let them live and die a natural death,

you’ll be bitten and left to die in agony,

and the mad dog pack

will then sniff out and search

for your children to eat, eat whole,

flesh, bones and soul.

These beasts will then retard the ones they

have not eaten in their schools of unlearning.

They will teach your children to do their hunting

and capture their own

to bring to them to devour,

and the dog, the mad dog,

will end up patting you

on the head and throwing you a bone.

Oddly, Pryor prefaces his reading of this poem by calling it comedy. Maybe this had something to do with what Reed mentioned in the article. He was too shy to publish his work, or, as it appears, even call it poetry. The mad dog of these lines, no doubt, represents a murderous white supremacist machine. A machine that could not only shoot down those prisoners from the gun towers on high, but also to justify it before the world. So Pryor used his voice here as a poet (later in the program as a comedian) to decry the blood on the walls and grounds of D-yard. This is what poetry does. What Pryor did.

Years later, I would hear another of his poems; this time recited by Yasin Bey aka Mos Def, participating in a documentary on Pryor. The poem, entitled “I See Black People,” was in one of the comedian’s diaries:

I’ve seen all kinds of black people

Light-skinned porters Black-skinned caddies Red bone bus drivers Fat red cooks and maids Shiny brown-skinned doctors Tinnie cigar shaped whiskey sailsman

White-skinned hustlers with gold in their teeth Fine yellow mamas in all girl bands I’ve seen big black dudes cry while sittin on the curb in the rain

Men and Woman spurtin washwords of nothin*

I’ve seen dimple faced dolls with no brains turn their noses at old, black church ladies who washed their floors so these cold-hearted bitches could wear lipstick

I’ve seen preachers eat chicken with both hands with their mouths already full.

I watched men die in gutters and spit on white ambulance drivers

But I Ain’t Dead Yet Muthafuckers

The poem not only shows the diversity of skin tones among black folk, it also shows that while they may be a collective, they are in no way a monolith. In these lines they hurt and heal; they suffer and hustle; they starve and stuff their faces, possessing the same dignity and wretchedness of all people. But he also acknowledges that their triumphs must be honored, having arrived here, without question, at tremendous cost. And this is what resonated with me all those years; he understood the tribe—the American tribe—better than most and peopled his performance with each and every one of them. I think of him and that performance and am reminded of André Breton’s words about poet Aimé Césaire, “And it is a black who is not only a black but all of man, who conveys all of man’s questionings, all of his anguish, all of his hopes and all of his ecstasies…” Thus, he, in the words of Whitman, “contains multitudes.”

So I ended the reading with Pryor’s poem and then mine. When finished, to my joy, the audience gave a heartfelt applause; and at that moment, I was happy to have come and read that night after all. It wound up being a tribute to the artist who was most responsible for my presence there in the first place. On my way out, a young woman came up and introduced herself. She was a knot of nervousness and couldn’t seem to find the words to make her point. After sweeping away the hair falling over her ear, she said, “I still don’t totally get how listening to comedy albums caused you to be a poet. But, I did love the poem.”

“Pryor’s or mine?” I smiled.

“The poems, I mean. All of them.”

We talked for a while and I did my best to explain to her that there’s a cadence and a musicality I hear in the works of Pryor that I can only describe as poetry. I mentioned that even his biographers David Henry & Joe Henry allude to this in their book Furious Cool. In the chapter “Is Stand-up Poetry?” they cite Eddie Tafoya, a professor of English at New Mexico who “makes the case that [Pryor’s] Live on Sunset Strip is a modern American answer to Dante’s Inferno.” Tafoya compares the bits in the stand-up routine with the Inferno’s cantos. Tafoya concludes that perhaps Pryor is “the only person of the last century able to venture into the depths of this particular Hell.” Similarly, editor Audrey Thomas McCluskey in his anthology of essays Richard Pryor: The Life and Legacy of a “Crazy” Black Man, mentions that author James Alan McPherson compared Pryor to the Greek poet Homer, stating that “McPherson believes that like Homer, Pryor drew upon the expressive language of everyday people and found a profundity in their wit and wisdom.” Or as I like to say, my father’s vernacular and the wit and wisdom of my old South Philly neighborhood, preachers and dope fiends alike. I did, however, admit to her that influences are at times difficult to understand, let alone explain, but what I know with certainty is that those albums continue to rotate in my head with every turn I write.